Enduring the Fires: From Anger to Patience

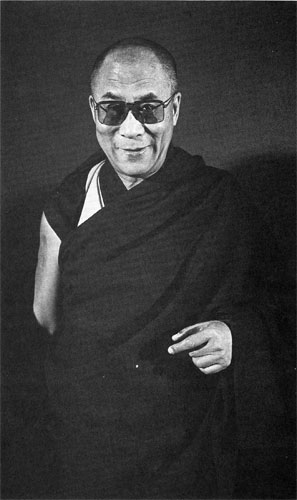

His Holiness the Dalai Lama in New York City, 1991. © Lynn Davis.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama in New York City, 1991. © Lynn Davis.

by His Holiness the Dalai lamam

Last August [1991--eds.], in a vast tent pitched in a meadow in the Valley of the Vizere in the Dordogne region of France, His Holiness the Dalai Lama expounded the dharma to an audience of five thousand. The week-long teaching took the form of a commentary on the Bodhicaryavatara(The Way of the Bodhisattva), the celebrated text written by the eighth-century Indian adept, scholar, and poet Shantideva.

The work of preparing the book of His Holiness' teachings was entrusted to the Padmakara Translation Group. The transcript was published in French by Albin Michel, under the title Comme un éclair déchire la nuit—"like a flash of lightning cutting through the night," a reference to Shantideva' s simile for the rarity of altruistic intentions. Recently, it was selected by one of the book clubs as "Major Book of the Month," an exceptional event for a book with a spiritual theme. Shambhala Publications will issue an English edition next year. The following excerpts on the practice of the paramita of patience come from the third chapter.

Patience is one of the vital elements in the bodhisattva's training. This third chapter of the Bodhicaryavatara, which deals with patience, and the eighth chapter, which deals with meditation, together explain the key points of bodhicitta.

1. Good works gathered in a thousand ages,

Such as deeds of generosity

Or offerings to the Blissful Ones:

A single flash of anger shatters them.

2. No evil is there similar to hatred,

Nor austerity to be compared with patience.

Steep yourself, therefore, in patience

In all ways, urgently, with zeal

As a destructive force there is nothing as strong as anger. An instant of anger can destroy all the positive action accumulated over thousands of kalpas through generosity, making offerings to the buddhas, keeping discipline, and so on. So we can say that there is no fault as serious as anger.

Patience, on the other hand, as a discipline which neutralizes anger, which prevents us from succumbing to it, and which appeases the suffering we endure from the heat of the negative emotions, is quite unrivaled. It is therefore of the utmost importance that we resolve to practice patience, and a lot of inspiration can be gained by reflecting on what is wrong with anger and on the advantages of patience.

Positive actions are difficult and infrequent. It is hard to have positive thoughts when our minds are influenced by emotions and confused by adverse circumstances. Negative thoughts arise by themselves, and it is rare that we do a positive action whose motivation, execution, and conclusion are perfectly pure. If our stock of hard-won positive actions is rendered powerless in an instant of anger, the loss is immeasurably more serious than that of some more abundant resource.

3. Those tormented by the pain of anger,

Will never know tranquility of mind,

Strangers to every joy and pleasure;

Sleep deserts them, they will never rest.

Anger chases all happiness away, and makes even the most peaceful features turn livid and ugly. It upsets our physical equilibrium, disturbs our rest, destroys our appetite, and makes us age prematurely. Happiness, peace, and sleep evade us, and we can no longer appreciate people who have helped us and deserve our trust and gratitude. Under the influence of anger, someone of normally good character changes completely and can no longer be counted on. Anger leads both oneself and others to ruin. But anyone who puts his energy into destroying anger will be happy in this life and in lives to come.

7. Getting what I do not want,

And that which hinders my desire:

There my mind finds fuel for misery,

Anger springs from it and beats me down.

8. Therefore I utterly destroy

The sustenance of this my enemy,

My foe, whose sole intention is

To bring me sorrow.

Whenever we think about someone who has wronged us, or someone who is doing (or might do) something we or our friends don't want—preventing us from having what we do want—our mind, at peace before, suddenly begins to feel slightly unsettled. This state of mind fuels our negative thoughts about that person. "What a nasty fellow he is!," we think, and our hatred grows stronger and stronger. It is this first stage, this unsettled feeling which kindles our hatred, that we should try to get rid of.

9. Come what may, then, I will never harm

My cheerful happiness of mind.

Depression never brings me what I want;

My virtue will be warped and marred by it.

10. If there is a cure when trouble comes,

What need is there for being sad?

And if no cure is to be found,

What use is there in sorrow?

We must make an effort to remain in a relaxed state of mind. If we cannot get rid of that unsettled feeling, it will feed our hatred, increase it, and eventually destroy us.

Hatred is far worse than any ordinary enemy. Of course, ordinary enemies harm us: that is why we call them enemies. But the harm they do is not just in order to make us unhappy; it is also meant to be of some help to themselves or their friends. Hatred, the inner enemy, however, has no other function but to destroy our positive actions and make us unhappy. That is why Shantideva calls it "My foe, whose sole intention is to bring me sorrow." From the moment it first appears, it exists for the sole purpose of harming us. So we should confront it with all the means we have, maintain a peaceful state of mind, and avoid getting upset.

What disconcerts us in the first place is that our wishes are not fulfilled. But remaining upset does nothing to help fulfill those wishes. So we neither fulfill our wishes, nor regain our cheerfulness! This disconcerted state, from which anger can grow, is most dangerous. We should try never to let our happiness be disturbed. Whether we are suffering at present or have suffered in the past, there is no reason to be unhappy. If we can remedy it, then why be unhappy? And if we cannot, there's no use in being unhappy about it—it's just one more thing to be unhappy about, which serves no purpose at all.

It is only natural that we don't like suffering. But if we can develop the willpower to bear difficulties, then we will grow more and more tolerant. There is nothing that does not get easier with practice. If we are very forbearing, then something we would normally consider very painful does not appear so bad after all. If we can develop our patience, we will be able to endure even major difficulties that befall us. But without such patient endurance, even the smallest thing becomes unbearable. A lot has to do with our attitude. All of us have some altruistic thoughts, limited though they may be. To develop such thoughts until our wish to help others becomes limitless is what we call bodhicitta. The main obstructions to this development are the wish to harm others, resentment, and anger. As the antidote to these, therefore, it is essential to meditate on patience. The more deeply we practice patience, the less chance there will be for anger to arise. Practicing patience is the best way to avoid getting angry.

Now, let's talk about love. In my opinion, all beings, starting with humans, appreciate love. Valuing love is a spontaneous feeling. Even animals like the people who are kind to them. When someone looks at you with a loving expression, it makes you feel happy, does it not? Love is a quality that is esteemed throughout all humanity, in all religions. Every religion, including Buddhism, describes its founder above all in terms of his capacity to love. Religions that talk about a Creator refer to his mercy. And the main quality of the Buddhist refuge is love.

When we describe a Pure Land filled with the presence of love, people feel like going there. But were we to describe those Pure Lands as places of warfare and fighting, people would no longer feel any desire to be reborn in such a place. People naturally value love and dislike harmful feelings and actions such as resentment, anger, fighting, stealing, coveting others' possessions, and wishing to harm others. So if love is something that all human beings like, it is certainly something that we can develop if we make the effort.

Many people think that to be patient and to bear loss is a sign of weakness. I think that is wrong. It is anger which is a sign of weakness, and patience a sign of strength. For example, a person arguing a point based on sound reasoning remains confident and may even smile while proving his cause. On the other hand, if his reasons are unsound and he is about to lose face, he gets angry, loses control, and starts talking nonsense. People rarely get angry if they are confident in what they are doing. Anger arises much more easily at moments of confusion.

22. I am not angry with my bile and other humors,

A fertile source of pain and suffering;

Why then be wroth with living beings,

Victims too of such conditions?

Suffering can result from both animate and inanimate causes. We may curse inanimate things like the weather, but it is with animate beings that we most often get angry. If we further analyze these animate causes that make us unhappy, we find that they are themselves influenced by other conditions. They are not making us angry simply because they want to. In this respect, because they are influenced by other conditions they are in fact powerless; so there is no need to get angry with them.

24. Never thinking: 'Now I will be angry,'

People are impulsively caught up in anger;

Irritation, likewise, comes

Though never plans to be experienced!

25. Every injury whatever,

The whole variety of evil deeds:

All arise induced by circumstances,

None are independent and autonomous

26. Yet these causes have no thought

Of brining something into being;

And that which is produced thereby,

Being mindless, has no thought of being so.

47. Those who harm me come against me:

Summoned by my evil karma.

They will be the ones who go to hell,

Am I not therefore the one to injure them?

When others harm us, it is the result of our own past actions, which in fact have instigated them—for, in future, they will suffer because of the harmful act we ourselves have instigated.

When others harm us, that gives us the chance to practice patience, and thus to purify numerous negative actions and accumulate much merit.

Since it is our enemies who give us this great opportunity, in reality they are helping us. But because we are the cause of the negative actions they commit, we are actually harming them. So if there is anyone to get angry with, it should be ourselves. We should never be angry with our enemies, regardless of their attitude, since they are so useful to us.

One might therefore wonder whether, by thus causing our enemies to accumulate negative actions, we accumulate negative actions ourselves; and whether our enemies in so helping us to practice patience have accumulated positive actions. But this is not the case. Although we were the cause for their negative actions, by our practicing patience we actually accumulate merit and will not take rebirth in the lower realms. As it is we who have been patient, that does not help our enemies. On the other hand, if we cannot stay patient when we are harmed, then the harm done by our enemies will not help anyone at all. Moreover, by losing patience and getting angry we transgress our vow to follow the discipline of a bodhisattva.

If, for example, a person condemned to death were to have his life spared in exchange for having his hands cut off, he would feel very happy. Similarly, when we have the chance to purify a great suffering by enduring a slight injury, we should accept it. If, unable to bear insults, we get angry, we are only creating worse suffering for the future. Difficult though it may be, we should try instead to think openly, on a vaster perspective, and not retaliate.

74. For the sake of my desired aims,

A thousand times I have endured the fires

And other pains of hell,

Achieving nothing for myself and others.

75. The present pains are nothing to compare with those,

And yet great benefits accrue from them.

These afflictions which dispel the troubles of all wandering beings:

I should only delight in them.

So far we have been, and are still, going through endless suffering, without this suffering doing us any good whatsoever. Now that we have promised to be good-hearted, we should try not to get angry when others insult us. Being patient may not be easy. It requires considerable concentration. But the result we achieve by enduring these difficulties will be sublime. That is something to be happy about!

90. The rigamarole of praise and reputation

Serves not to increase merit nor the span of life,

Bestowing neither health nor strength of body,

It contributes nothing to the body's ease.

98. Praise and compliments disturb me,

And soften my revulsion with samsara:

I begin to covet others' qualities and

Every excellence is thereby spoiled.

Praise, if you think about it, is actually a distraction. For example, in the beginning one may be a simple, humble monk, content with little. Later on people may start to praise one, saying, "He's a lama," and one begins to feel a bit more proud and to be more self-conscious in how one feels and behaves. Then the eight worldly considerations become stronger, do they not, and the praise we receive distracts us, destroying our renunciation.

Again, at first when we have little to compare ourselves with, we do not feel jealous of others. But later we begin to "grow some hair," and as our status increases so does our rivalry with others in important positions. We feel jealous of anyone with good qualities, and in the end this destroys our own good qualities. Being praised is not really a good thing—it can be the source of negative actions.

99. Those who stay close by me, then,

To ruin my good name and cut me down to size,

Are they not my guardians saving me

From falling into realms of sorrow?

As our real goal is enlightenment, we should not be angry with our enemies, who in fact dispel all the obstacles to our attaining enlightenment.

101. They, like Buddha's very blessing,

Bar my way, determined as I am

To plunge myself in suffering:

How could I be angry with them?

102. We should not be angry, saying,

'They are an obstacle to virtue,'

Patience is the peerless austerity,

And is this not my chosen path?

It is no use saying that our enemies are preventing us from practicing, and that is why we get angry. For if we truly want to practice, there is no practice more important than patience. We cannot pretend to practice without patience.

If we cannot bear the harm our enemies do to us, and get angry instead, we are obstructing our own achievement of an immensely positive action. Nothing can exist without a cause, and the practice of patience could not exist without there being people who do us harm. How, then, can we call such people obstacles to our practice of patience, which is one of the fundamental practices of a Mahayana practitioner? We can hardly call a beggar an obstacle to generosity.

There are so many charitable causes, such as beggars, in the world; whereas those who make us angry and test our patience are very few—especially if we avoid harming others. So when we encounter these rare enemies, we should appreciate them.

107. Like a treasure found at home,

Enriching me without fatigue,

Enemies are helpers in the bodhisattva life,

I should take delight in them.

When we have been patient toward an enemy, we should dedicate the fruit of this practice of patience to him, because he is the cause of the practice. He has been very kind to us. We might think, why does he deserve this dedication when he had no intention to make us practice patience? But if objects need have an intention before they deserve our respect, then in that case the dharma itself, which points out the cessation of suffering and is the cause of happiness, yet has no intention of helping us, should not be worthy of respect.

We might then think that our enemy is undeserving because, unlike the dharma, he actually wishes to harm us. But if everyone was as kind and well-intentioned as a doctor, how could we ever practice patience? And when a doctor, intending to cure us, hurts us by amputating a limb, cutting us open, or pricking us with needles, we do not think of him as an enemy and get angry with him, so we do not practice patience toward him. But enemies are those who intend to harm us, and it is because of that that we are able to practice patience toward them.

If we really take refuge in the buddhas, then we should respect their wishes. After all, in ordinary life it is normal to adapt in some way to one's friends and respect their wishes. The ability to do so is considered a good quality. If, on the one hand, we say that we have heartfelt devotion and take refuge in the Buddha, dharma, and sangha, but on the other hand, in our actual actions, we take no notice of what displeases them, and just walk over them, that is truly sad. We are prepared to conform to the standards of ordinary people but not to those of the buddhas and bodhisattvas. How miserable! If, for example, a Christian truly loves God, then he should practice love toward all his fellow human beings. Otherwise, he is failing to practice his religion: his words and deeds contradict each other.

In general, it is the notion of enemies that is the main obstacle to bodhicitta. If we can transform an enemy into someone toward whom we feel respect and gratitude, then our practice will naturally progress, like water following a downhill course.

To be patient means not to get angry with those who harm us and to have compassion. That is not to say that we should let them do what they like. For example, we Tibetans have undergone great difficulties at the hands of others. But we are not angry with them, since if we get angry we can only lose. This is why we are practicing patience. But we are not going to let injustice and oppression go unnoticed.

Image 1: His Holiness the Dalai Lama in New York City, 1991. © Lynn Davis.

read full article here

Last August [1991--eds.], in a vast tent pitched in a meadow in the Valley of the Vizere in the Dordogne region of France, His Holiness the Dalai Lama expounded the dharma to an audience of five thousand. The week-long teaching took the form of a commentary on the Bodhicaryavatara(The Way of the Bodhisattva), the celebrated text written by the eighth-century Indian adept, scholar, and poet Shantideva.

The work of preparing the book of His Holiness' teachings was entrusted to the Padmakara Translation Group. The transcript was published in French by Albin Michel, under the title Comme un éclair déchire la nuit—"like a flash of lightning cutting through the night," a reference to Shantideva' s simile for the rarity of altruistic intentions. Recently, it was selected by one of the book clubs as "Major Book of the Month," an exceptional event for a book with a spiritual theme. Shambhala Publications will issue an English edition next year. The following excerpts on the practice of the paramita of patience come from the third chapter.

Patience is one of the vital elements in the bodhisattva's training. This third chapter of the Bodhicaryavatara, which deals with patience, and the eighth chapter, which deals with meditation, together explain the key points of bodhicitta.

1. Good works gathered in a thousand ages,

Such as deeds of generosity

Or offerings to the Blissful Ones:

A single flash of anger shatters them.

2. No evil is there similar to hatred,

Nor austerity to be compared with patience.

Steep yourself, therefore, in patience

In all ways, urgently, with zeal

As a destructive force there is nothing as strong as anger. An instant of anger can destroy all the positive action accumulated over thousands of kalpas through generosity, making offerings to the buddhas, keeping discipline, and so on. So we can say that there is no fault as serious as anger.

Patience, on the other hand, as a discipline which neutralizes anger, which prevents us from succumbing to it, and which appeases the suffering we endure from the heat of the negative emotions, is quite unrivaled. It is therefore of the utmost importance that we resolve to practice patience, and a lot of inspiration can be gained by reflecting on what is wrong with anger and on the advantages of patience.

Positive actions are difficult and infrequent. It is hard to have positive thoughts when our minds are influenced by emotions and confused by adverse circumstances. Negative thoughts arise by themselves, and it is rare that we do a positive action whose motivation, execution, and conclusion are perfectly pure. If our stock of hard-won positive actions is rendered powerless in an instant of anger, the loss is immeasurably more serious than that of some more abundant resource.

3. Those tormented by the pain of anger,

Will never know tranquility of mind,

Strangers to every joy and pleasure;

Sleep deserts them, they will never rest.

Anger chases all happiness away, and makes even the most peaceful features turn livid and ugly. It upsets our physical equilibrium, disturbs our rest, destroys our appetite, and makes us age prematurely. Happiness, peace, and sleep evade us, and we can no longer appreciate people who have helped us and deserve our trust and gratitude. Under the influence of anger, someone of normally good character changes completely and can no longer be counted on. Anger leads both oneself and others to ruin. But anyone who puts his energy into destroying anger will be happy in this life and in lives to come.

7. Getting what I do not want,

And that which hinders my desire:

There my mind finds fuel for misery,

Anger springs from it and beats me down.

8. Therefore I utterly destroy

The sustenance of this my enemy,

My foe, whose sole intention is

To bring me sorrow.

Whenever we think about someone who has wronged us, or someone who is doing (or might do) something we or our friends don't want—preventing us from having what we do want—our mind, at peace before, suddenly begins to feel slightly unsettled. This state of mind fuels our negative thoughts about that person. "What a nasty fellow he is!," we think, and our hatred grows stronger and stronger. It is this first stage, this unsettled feeling which kindles our hatred, that we should try to get rid of.

9. Come what may, then, I will never harm

My cheerful happiness of mind.

Depression never brings me what I want;

My virtue will be warped and marred by it.

10. If there is a cure when trouble comes,

What need is there for being sad?

And if no cure is to be found,

What use is there in sorrow?

We must make an effort to remain in a relaxed state of mind. If we cannot get rid of that unsettled feeling, it will feed our hatred, increase it, and eventually destroy us.

Hatred is far worse than any ordinary enemy. Of course, ordinary enemies harm us: that is why we call them enemies. But the harm they do is not just in order to make us unhappy; it is also meant to be of some help to themselves or their friends. Hatred, the inner enemy, however, has no other function but to destroy our positive actions and make us unhappy. That is why Shantideva calls it "My foe, whose sole intention is to bring me sorrow." From the moment it first appears, it exists for the sole purpose of harming us. So we should confront it with all the means we have, maintain a peaceful state of mind, and avoid getting upset.

What disconcerts us in the first place is that our wishes are not fulfilled. But remaining upset does nothing to help fulfill those wishes. So we neither fulfill our wishes, nor regain our cheerfulness! This disconcerted state, from which anger can grow, is most dangerous. We should try never to let our happiness be disturbed. Whether we are suffering at present or have suffered in the past, there is no reason to be unhappy. If we can remedy it, then why be unhappy? And if we cannot, there's no use in being unhappy about it—it's just one more thing to be unhappy about, which serves no purpose at all.

It is only natural that we don't like suffering. But if we can develop the willpower to bear difficulties, then we will grow more and more tolerant. There is nothing that does not get easier with practice. If we are very forbearing, then something we would normally consider very painful does not appear so bad after all. If we can develop our patience, we will be able to endure even major difficulties that befall us. But without such patient endurance, even the smallest thing becomes unbearable. A lot has to do with our attitude. All of us have some altruistic thoughts, limited though they may be. To develop such thoughts until our wish to help others becomes limitless is what we call bodhicitta. The main obstructions to this development are the wish to harm others, resentment, and anger. As the antidote to these, therefore, it is essential to meditate on patience. The more deeply we practice patience, the less chance there will be for anger to arise. Practicing patience is the best way to avoid getting angry.

Now, let's talk about love. In my opinion, all beings, starting with humans, appreciate love. Valuing love is a spontaneous feeling. Even animals like the people who are kind to them. When someone looks at you with a loving expression, it makes you feel happy, does it not? Love is a quality that is esteemed throughout all humanity, in all religions. Every religion, including Buddhism, describes its founder above all in terms of his capacity to love. Religions that talk about a Creator refer to his mercy. And the main quality of the Buddhist refuge is love.

When we describe a Pure Land filled with the presence of love, people feel like going there. But were we to describe those Pure Lands as places of warfare and fighting, people would no longer feel any desire to be reborn in such a place. People naturally value love and dislike harmful feelings and actions such as resentment, anger, fighting, stealing, coveting others' possessions, and wishing to harm others. So if love is something that all human beings like, it is certainly something that we can develop if we make the effort.

Many people think that to be patient and to bear loss is a sign of weakness. I think that is wrong. It is anger which is a sign of weakness, and patience a sign of strength. For example, a person arguing a point based on sound reasoning remains confident and may even smile while proving his cause. On the other hand, if his reasons are unsound and he is about to lose face, he gets angry, loses control, and starts talking nonsense. People rarely get angry if they are confident in what they are doing. Anger arises much more easily at moments of confusion.

22. I am not angry with my bile and other humors,

A fertile source of pain and suffering;

Why then be wroth with living beings,

Victims too of such conditions?

Suffering can result from both animate and inanimate causes. We may curse inanimate things like the weather, but it is with animate beings that we most often get angry. If we further analyze these animate causes that make us unhappy, we find that they are themselves influenced by other conditions. They are not making us angry simply because they want to. In this respect, because they are influenced by other conditions they are in fact powerless; so there is no need to get angry with them.

24. Never thinking: 'Now I will be angry,'

People are impulsively caught up in anger;

Irritation, likewise, comes

Though never plans to be experienced!

25. Every injury whatever,

The whole variety of evil deeds:

All arise induced by circumstances,

None are independent and autonomous

26. Yet these causes have no thought

Of brining something into being;

And that which is produced thereby,

Being mindless, has no thought of being so.

47. Those who harm me come against me:

Summoned by my evil karma.

They will be the ones who go to hell,

Am I not therefore the one to injure them?

When others harm us, it is the result of our own past actions, which in fact have instigated them—for, in future, they will suffer because of the harmful act we ourselves have instigated.

When others harm us, that gives us the chance to practice patience, and thus to purify numerous negative actions and accumulate much merit.

Since it is our enemies who give us this great opportunity, in reality they are helping us. But because we are the cause of the negative actions they commit, we are actually harming them. So if there is anyone to get angry with, it should be ourselves. We should never be angry with our enemies, regardless of their attitude, since they are so useful to us.

One might therefore wonder whether, by thus causing our enemies to accumulate negative actions, we accumulate negative actions ourselves; and whether our enemies in so helping us to practice patience have accumulated positive actions. But this is not the case. Although we were the cause for their negative actions, by our practicing patience we actually accumulate merit and will not take rebirth in the lower realms. As it is we who have been patient, that does not help our enemies. On the other hand, if we cannot stay patient when we are harmed, then the harm done by our enemies will not help anyone at all. Moreover, by losing patience and getting angry we transgress our vow to follow the discipline of a bodhisattva.

If, for example, a person condemned to death were to have his life spared in exchange for having his hands cut off, he would feel very happy. Similarly, when we have the chance to purify a great suffering by enduring a slight injury, we should accept it. If, unable to bear insults, we get angry, we are only creating worse suffering for the future. Difficult though it may be, we should try instead to think openly, on a vaster perspective, and not retaliate.

74. For the sake of my desired aims,

A thousand times I have endured the fires

And other pains of hell,

Achieving nothing for myself and others.

75. The present pains are nothing to compare with those,

And yet great benefits accrue from them.

These afflictions which dispel the troubles of all wandering beings:

I should only delight in them.

So far we have been, and are still, going through endless suffering, without this suffering doing us any good whatsoever. Now that we have promised to be good-hearted, we should try not to get angry when others insult us. Being patient may not be easy. It requires considerable concentration. But the result we achieve by enduring these difficulties will be sublime. That is something to be happy about!

90. The rigamarole of praise and reputation

Serves not to increase merit nor the span of life,

Bestowing neither health nor strength of body,

It contributes nothing to the body's ease.

98. Praise and compliments disturb me,

And soften my revulsion with samsara:

I begin to covet others' qualities and

Every excellence is thereby spoiled.

Praise, if you think about it, is actually a distraction. For example, in the beginning one may be a simple, humble monk, content with little. Later on people may start to praise one, saying, "He's a lama," and one begins to feel a bit more proud and to be more self-conscious in how one feels and behaves. Then the eight worldly considerations become stronger, do they not, and the praise we receive distracts us, destroying our renunciation.

Again, at first when we have little to compare ourselves with, we do not feel jealous of others. But later we begin to "grow some hair," and as our status increases so does our rivalry with others in important positions. We feel jealous of anyone with good qualities, and in the end this destroys our own good qualities. Being praised is not really a good thing—it can be the source of negative actions.

99. Those who stay close by me, then,

To ruin my good name and cut me down to size,

Are they not my guardians saving me

From falling into realms of sorrow?

As our real goal is enlightenment, we should not be angry with our enemies, who in fact dispel all the obstacles to our attaining enlightenment.

101. They, like Buddha's very blessing,

Bar my way, determined as I am

To plunge myself in suffering:

How could I be angry with them?

102. We should not be angry, saying,

'They are an obstacle to virtue,'

Patience is the peerless austerity,

And is this not my chosen path?

It is no use saying that our enemies are preventing us from practicing, and that is why we get angry. For if we truly want to practice, there is no practice more important than patience. We cannot pretend to practice without patience.

If we cannot bear the harm our enemies do to us, and get angry instead, we are obstructing our own achievement of an immensely positive action. Nothing can exist without a cause, and the practice of patience could not exist without there being people who do us harm. How, then, can we call such people obstacles to our practice of patience, which is one of the fundamental practices of a Mahayana practitioner? We can hardly call a beggar an obstacle to generosity.

There are so many charitable causes, such as beggars, in the world; whereas those who make us angry and test our patience are very few—especially if we avoid harming others. So when we encounter these rare enemies, we should appreciate them.

107. Like a treasure found at home,

Enriching me without fatigue,

Enemies are helpers in the bodhisattva life,

I should take delight in them.

When we have been patient toward an enemy, we should dedicate the fruit of this practice of patience to him, because he is the cause of the practice. He has been very kind to us. We might think, why does he deserve this dedication when he had no intention to make us practice patience? But if objects need have an intention before they deserve our respect, then in that case the dharma itself, which points out the cessation of suffering and is the cause of happiness, yet has no intention of helping us, should not be worthy of respect.

We might then think that our enemy is undeserving because, unlike the dharma, he actually wishes to harm us. But if everyone was as kind and well-intentioned as a doctor, how could we ever practice patience? And when a doctor, intending to cure us, hurts us by amputating a limb, cutting us open, or pricking us with needles, we do not think of him as an enemy and get angry with him, so we do not practice patience toward him. But enemies are those who intend to harm us, and it is because of that that we are able to practice patience toward them.

If we really take refuge in the buddhas, then we should respect their wishes. After all, in ordinary life it is normal to adapt in some way to one's friends and respect their wishes. The ability to do so is considered a good quality. If, on the one hand, we say that we have heartfelt devotion and take refuge in the Buddha, dharma, and sangha, but on the other hand, in our actual actions, we take no notice of what displeases them, and just walk over them, that is truly sad. We are prepared to conform to the standards of ordinary people but not to those of the buddhas and bodhisattvas. How miserable! If, for example, a Christian truly loves God, then he should practice love toward all his fellow human beings. Otherwise, he is failing to practice his religion: his words and deeds contradict each other.

In general, it is the notion of enemies that is the main obstacle to bodhicitta. If we can transform an enemy into someone toward whom we feel respect and gratitude, then our practice will naturally progress, like water following a downhill course.

To be patient means not to get angry with those who harm us and to have compassion. That is not to say that we should let them do what they like. For example, we Tibetans have undergone great difficulties at the hands of others. But we are not angry with them, since if we get angry we can only lose. This is why we are practicing patience. But we are not going to let injustice and oppression go unnoticed.

Image 1: His Holiness the Dalai Lama in New York City, 1991. © Lynn Davis.

read full article here